I started typing on a mechanical typewriter probably 45 years ago, and never learned to touch type. Over the years, the old-school, wow-but-it-makes-a-lot-of-noise typewriter was replaced by an electric version, and eventually, with a computer – a Sinclair ZX81 – which had a weird membrane keyboard that needed a hefty and accurate push of the fingertips to register a key-press.

Even after the arrival of ‘real’ computer keyboards attached to 386 powerhouses, and through to the recent present, my typing style was still hunt-and-peck. For sure, I was a fast-enough typist (about 35 wpm on a good day with a prevailing wind), not really having to look down all that much, but I definitely needed to glance down to see what button I was pressing pretty often. And I was glancing down a lot, it seemed; something I discovered during repeated attempts to learn to touch type.

About 10 years ago, I stumbled across a podcast called Gnu World Order by a nice chap who goes by the moniker Klaatu, and he mentioned a few times that he used the Dvorak keyboard layout. I’d seen mention of Dvorak and systems like Colemak during OS installations and noodling around the keyboard settings control panels, preference panes and configurations of various ‘puters over the years, and kinda knew what they were. So, when I resolved for the 47th time to finally learn touch typing, I thought I’d give Dvorak a try.

My logic was as follows:

- Whenever I tried to touch type, there came a time when I was in a tearing hurry to type something, and would invariably revert to looking down at the (QWERTY) keyboard in front of me. Thus, I was never really under massive pressure to mend my hunt-and-peck ways.

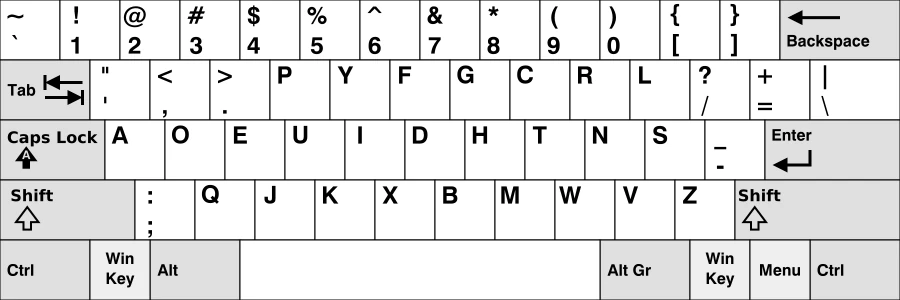

- By changing the keyboard layout in software and retaining the physical QWERTY keyboard, looking down at the thing would do me no good at all. Pressing the ‘e’ key would render a full stop (or period, for the Merkans), the ‘t’ key would produce ‘y’ and so on. In other words, I had to learn where the letters were that I needed by practice and simple repetition.

- Not many people use Dvorak, which placed me immediately into a minority niche, and that’s comfortable for me. If there’s a pack, I try not to follow it. This I fully recognise as a pure conceit.

- I read that in some opinions, the Dvorak layout’s placing of common letters on the home row meant an inherent advantage in speed. This struck me then as ‘gaming chair’ logic, in that by adopting a certain thing like wot the pros do, any level of average ability would be improved magically. Call it the Ping golf club syndrome, if you like: my handicap will lose a couple of points simply by buying expensive kit. So, the idea that using Dvorak layout would automatically make me faster, eventually, was treated with some suspicion. (To date, those suspicions were well-founded.)

To get me started, I looked on the internet for the Mavis Beacon Typing Tutor, an act (and an admission here) that ages me. Whatever happened to Mavis? (Or perhaps she’s still going?) And was it Mr Beacon who was the brains behind the outfit, she just being the front? In the same way, as every fool knows, it’s Mrs Kipling who’s the baking mastermind; Mr Kipling is just the brand.

In the absence of the much-lamented Mrs Beacon, I came across several tools and websites that would feed words and letters at me in ways designed specifically for Dvorak users. There are several that interested parties may wish to try, but the one I return to is keybr.com, which users can pay for if they find it useful.

To begin with, the tutors I tried (at least) start you off with simple words that use the most common letters, and therefore, on a Dvorak keyboard, the home row – those are the keys that the four fingers of each hand naturally sit on. The right hand, for example, from index to little finger, give you htns, while the left hand, in the same order, supply ueoa. With those, there are hundreds if not thousands of words to practise, and the platform like the latter-day Mrs Beacon, keybr.com, will display them on-screen and let you type them. Many, many, many times. Once the required words per minute has been reached on all the home row keys, it will add a bonus letter, like, say, ‘c’ which gives you gazillions more words. And so on and so forth.

Initially, I aimed at 35 words per minute using the new layout, given that it was about that speed that I could manage using QWERTY. A couple of months later, at around 30 mins to an hour a day practice, I got there, using every key on the keyboard, including punctuation. Then, I reset the whole shebang to 60 words a minute and started again. As of the time of writing, I usually manage around 72 words per minute, but – and this is, I think, the big deal – I’m much more accurate than what keybr.com tells me is an average typist who manages 70wpm. The typing test I did but a moment ago was completed at 97.82% accuracy, which the silent algorithm tells me puts me in the top 10% most accurate typists. So, you see, I really am very, very special.

The issue with accuracy is that, unless you’re really trusting of your spelling correction software and letting it do its thing as you type, all those mistakes need krekshun. So even if you can blaze away at 120wpm (the techno of typists, if you will), having to go back and sort stuff out slows down the time it takes between blank page and finished text. Which kinda negates the point, to some extent, of being able to type so quickly. This argument seems to be a justification of not being wildly fast, but being very accurate, like turning up to a wedding in jeans, but very very good shoes. Is it a minor detail? But, I guess the idea is that one’s speed should climb alongside an improving, or at least stationary accuracy rate.

A couple of other things. First, keyboards. I seem to have ended up using clicky, mechanical keyboards that make a racket, and I seem to prefer low-profile variants. My current beastie is a Keychron K-15 Pro, which keyboard nerds might recognise as an ‘Alice’ layout number. That means the keyboard is split into two banks of keys, one for each hand, and each bank is angled slightly inwards. The switches I use (those are the mechanisms under the bits of plastic with letters printed on them) are coloured blue, which identifies them as the type that makes a distinct ‘click’ whenever the key is activated. But none of these things is essential to learn to touch type on a QWERTY or Dvorak keyboard. Having said that, typing on a laptop is, comparatively, pretty horrible, unless you source an older Lenovo ThinkPad (or even a pre-Lenovo IBM ThinkPad), the ones that come with a proper-ish keyboard.

A secondary consideration, and one that’s made my typing life a lot smoother and the production of words onscreen a whole heap easier, is learning how to use a proper text editor. Microsoft Frickin Word, or Pages on a Mac to name but two, are great at embedding video into a mail-merged presentation deck, but seem to have forgotten they were designed to edit text. Instead I advocate learing something like Emacs or Vim. I use the former, by accident rather than design. And by really getting to grips with the software, steps like skipping back a word (or any number of words), or forward a sentence, or up three paragraphs can be accomplished by keyboard shortcuts. That is, no mouse: hands stay on the home row the whole time. You wouldn’t believe what a time saver this sort of thing is over the course of a day spent writing and editing text. Swapping two words (split infinitives, anyone?), or two letters around (wierd how weird is written, no?), shifting a whole paragraph up, spell checking, search and replace – all are accomplished in a few presses and key combinations. Mouses are over-rated around these parts.

But Emacs, text editing and so on is a subject for a different blog post. So, enough.

On a pedantic note, how to pronounce Dvorak? Being a certified twat, a tend to pronounce it like the Czech composer’s name (strictly, Dvořák), like “Vorjack” but with a soft ‘j’ as in “served in a rosemary and thyme jus”. But the computer world seems to prefer Vor-ack. Or Duh-vor-(j)ack. So who knows? Perhaps I should have opted for the Colemak keyboard layout? It would have been easier to say.

The Dvorak layout isn’t entirely without its faults. Certain punctuation marks are a pain in the arse to find if you happen to do a lot of computer coding, or as is true in my case, need them in order to write about ‘puters. (N.B. There is a Dvorak variant designed just for programmers.) The tilde (~) is a stretch, I’m forever mixing up ? and +, and I still get the full stop and p keys the wrong way around. For things like backslash and pipe (‘\’ and ‘|’) I tend to still look down. On my proper desktop keyboard, I’ve swapped all the keycaps around (the bits of plastic with the letters printed on them), but on laptops, I’ve had to resort to buying and applying little stickers over the existing keys. You can buy laptops that a) ship with Dvorak keyboards and b) will run A Proper Operating System natively, by the way, but I can’t really justify the expense.

The actual process of practising typing for a few minutes is an oddly restful experience, requiring a particular mixture of concentration and mindfulness that’s very calming. Anyone who’s ever practised a musical instrument will be acquainted with this state of mind. So, these days, practising typing is as close as I often get to meditation, or zoning out.

Given so much of what we do is all dijjitall these days, learning to type should be enforced, sorry, encouraged in schools. But I guess these days, the development of bionic thumbs is enough for the kids to use their ever-present phones. For anyone cursed with a sedentary, computer-based job that isn’t knocking up Rust apps, learning to type is kinda like learning the tools of any trade. I did get away with not bothering to learn for 40 years, mind, so I shouldn’t be casting around being the big dictator of others’ lives.